I was just going through my old wooden box of antique paper photographs from the late 1800s and early 1900s, which is something I haven’t done for a few years. I’d forgotten how good my collection is. I’ve got lots of children with toys, tea parties, freaky old people, dead people, and tons of nuns. This is in addition of my ‘hard’ image collection of daguerreotypes, ambrotypes and tintypes, which go back as far as the 1840s. (Photography was invented by Louis Daguerre in 1839, by the way.)

I’m going to get a scanner and start scanning and posting an image a week from my collection. (I know, I started doing that with my daguerreotypes ages ago, and it lasted about two weeks…but I was in the middle of moving and it fell off the back burner.)

Many people think antique photographs are creepy. People rarely smiled, and for the most part they looked humourless and dour and burdened by the sheer effort of living. And it was, comparatively speaking, a hard life they were living. Basic grooming, for example, took monumental effort on their part. They had to haul water and boil it in order to take a bath. Laundry would have been a nightmare – they had all those kids (many of whom died, but still) and the women wore so many layers of huge clothing. All those layers for all those people had to be washed by hand, without the benefit of running water. (The Victorians were understandably smellier than us.)

I’m sure they smiled though, just not for the camera. When you think about it, why do WE smile for the camera? My son says in a couple of hundred years people will be collecting photographs from our era and wondering why we smiled so much.

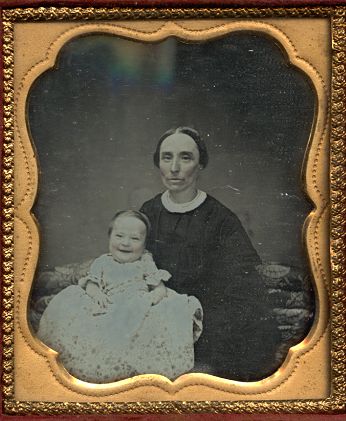

This week’s antique photograph is a daguerreotype, which dates back to the late 1840s or early 1850s. I’ve chosen this one for two reasons: I already have a scan of it, and it’s not as scary as many of my images, because one of the two subjects is smiling (I’ll post the scarier ones once I’ve lured you in a bit).

A couple of quick facts about daguerreotypes, in case you’ve never seen one:

- they’re 3-dimensional objects in that the image is ‘printed’ on a silvered copper plate encased in glass, a brass frame and a folding case, often with a velvet pad opposite the image;

- each one is unique, since in essence the ‘negative’ is consumed in the making of the ‘print’;

- if you tilt a daguerreotype, you can see the image change from positive to negative and back again;

- many of the images being sold as daguerreotypes in antique shops or ebay are actually tintypes or ambrotypes; daguerreotypes have a mirrored quality and much greater depth and richness than ambrotypes or tintypes, which are flat.

- the original daguerrean era was short: 1839 to the 1860s. Dags were then replaced by ambrotypes. There are a few contemporary daguerreotypists working today, one of whom lives in Toronto and offers daguerreotype-making workshops. His name is Mike Robinson.

And now, without further ado, here is the antique image of the week:

See, that wasn’t so creepy, was it? The woman doesn’t exactly look like a barrel of laughs, but this image is all about the baby. This dag is poorly composed, there’s lots of wasted space above the subjects, and it lacks the richness and depth of a great dag. But it’s special to me because it’s my only smiler.

IMO old photographs are more interesting because the people in them don’t smile. For some reason I am always intrigued by old photos.

Thanks for sharing this one. The contrast in facial expressions is huge and that is probably why I can’t stop staring at the picture

The contrast is quite interesting, now that you mention it Dakota. Glad you like it. I wonder if I should be worried about the resounding silence from everybody else. Although one faithful reader did email me to extend the offer of a scanner…so he must really want to see more old photos. (He expressly mentioned dead people.)

Bromine-sensitized and Mercury-developed daguerreotypes have relatively (compared to Becquerel-processed dags) fast exposure times; the sitting might be anywhere from 10-60 seconds depending on the lighting conditions.

Asking someone to hold a smile for that length of time is out of the question.

My daguerreotype exposures are longer than those typical of the Daguerreian era because I choose not to use Mercury and Bromine. Instead, I use the Becquerel process which makes my fastest exposure to date about 90 seconds.

Another idea is that the medium was very new and could only be compared to a portrait sitting. Smiles were rarely recorded in paintings for similar reasons.

-Jonathan

shinyphotos.com

Jonathan, thanks for dropping by – we don’t get a lot of actual working daguerreotypists around here! Would you happen to know the exposure times of cabinet photos and CDVs? I notice there aren’t many smilers in those photographs either.

I don’t know the exposure times for CDV or Cabinet except to say that they were vastly shorter than daguerreotype exposures. Perhaps the non-smile was a social thing.

-Jonathan

hey there… you mean there are other people out there interested in old photos!!!!!

any one interested in sharing old images & chating I have several interesting items…

Robert

rare-photos@hotmail.com